National Treasure: Portrait of Saichō – Heian Period, Ichijō-ji Temple (Kasai City, Hyōgo Prefecture), Public Domain

【Summary 】

Japanese Buddhism has shaped the nation for more than a millennium, and few figures embody its spirit more than Saichō, the founder of the Tendai tradition on Mount Hiei. This article explores the historical background leading to Saichō’s thought, including the evolution of Buddhism in Japan, the unique relationship between Saichō and Kūkai, and why Mount Hiei became the cradle of many influential Buddhist leaders.

A central theme is Saichō’s famous phrase, “Light up your corner,” from his text Sange Gakushō-shiki. Contrary to modern interpretations that romanticize the phrase as simply “doing your best where you are,” the deeper meaning emphasizes the cultivation of dōshin—the sincere aspiration for enlightenment. Saichō argued that people who cultivate this inner intention are the true national treasures, surpassing material wealth or social prominence.

This concept aligns with Buddhist ideas of Buddha-nature, which holds that all individuals possess inherent dignity and potential for awakening. Saichō’s teaching encourages people not to undervalue themselves or others, and to refine the innate clarity within. Tendai Buddhism today promotes this through the “Light Up Your Corner Movement,” advocating practical daily acts such as kindness, sincerity, and responsibility as modern forms of bodhisattva practice.

The article concludes with a provocative hint: the widely accepted reading “Light up one’s corner” may actually be a thousand-year misinterpretation—an insight to be explored in the next installment.

【Main Text 】

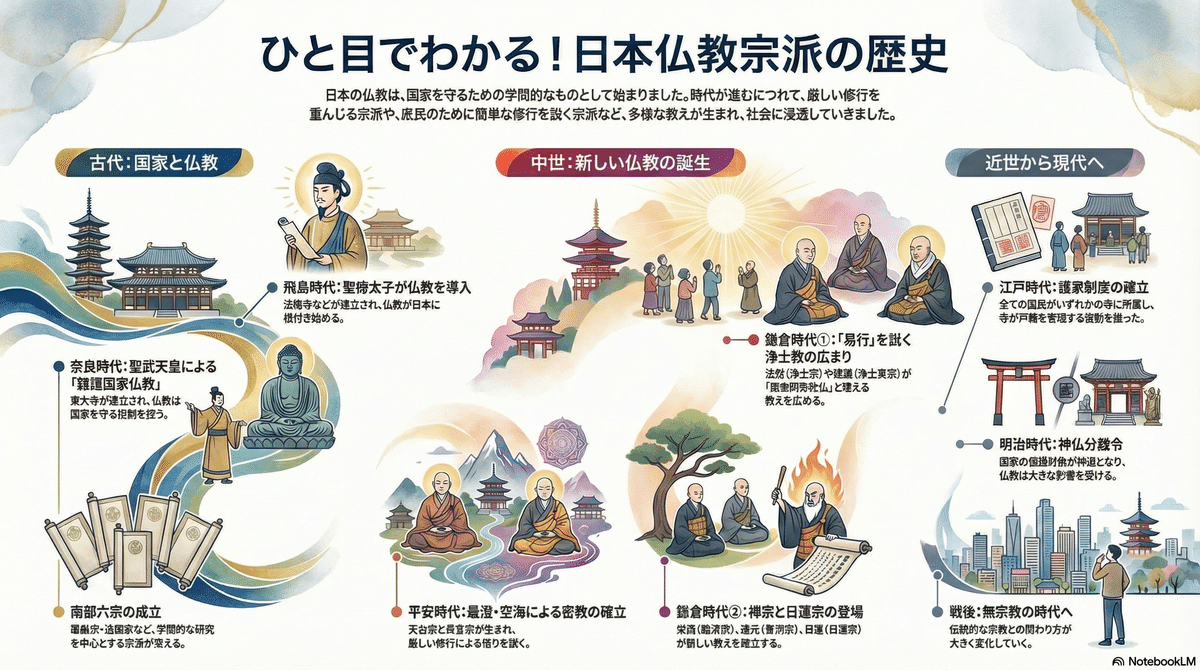

Japanese Buddhism has been valued in Japan from Prince Shōtoku until the 1871 Shinto–Buddhist Separation Order. If we describe the history in a textbook style, it progresses as follows:

Asuka period — Prince Shōtoku — Hōryū-ji, Chūgū-ji, Shitennō-ji.

Nara period — Emperor Shōmu — Buddhism for protecting the state — Tōdai-ji, provincial temples and nunneries;

the Six Nara Schools (Kegon, Hossō, Ritsu, Sanron, Jōjitsu, Kusha) — academic.

The incident of the oracle at Usa Hachiman Shrine leading to Dōkyō’s expulsion.

Heian period — separation from the Six Nara Schools — “people attain enlightenment through harsh training”;

Saichō and Kūkai (Tendai and Shingon).

Then, due to the belief in the Latter Age of Degeneration, Pure Land teachings (Kūya) appeared: “Namu Amida Butsu.”

Kamakura period — Easy practice;

influenced by Pure Land — Hōnen (Jōdo-shū), Shinran (Jōdo Shinshū), Ippen (Ji-shū);

Nichiren (Nichiren-shū);

trade with China brought Zen — Eisai (Rinzai), Dōgen (Sōtō).

Edo period — all Japanese became parishioners of local temples (temples functioned like today’s city offices).

Meiji period — Shinto placed above Buddhism because of the separation order.

Now, I want to speak about Saichō, the founder of Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei. Among historical portraits in Japan, few show personality as clearly as his. His transparent complexion and quietly closed eyes seem to reveal his sincerity.

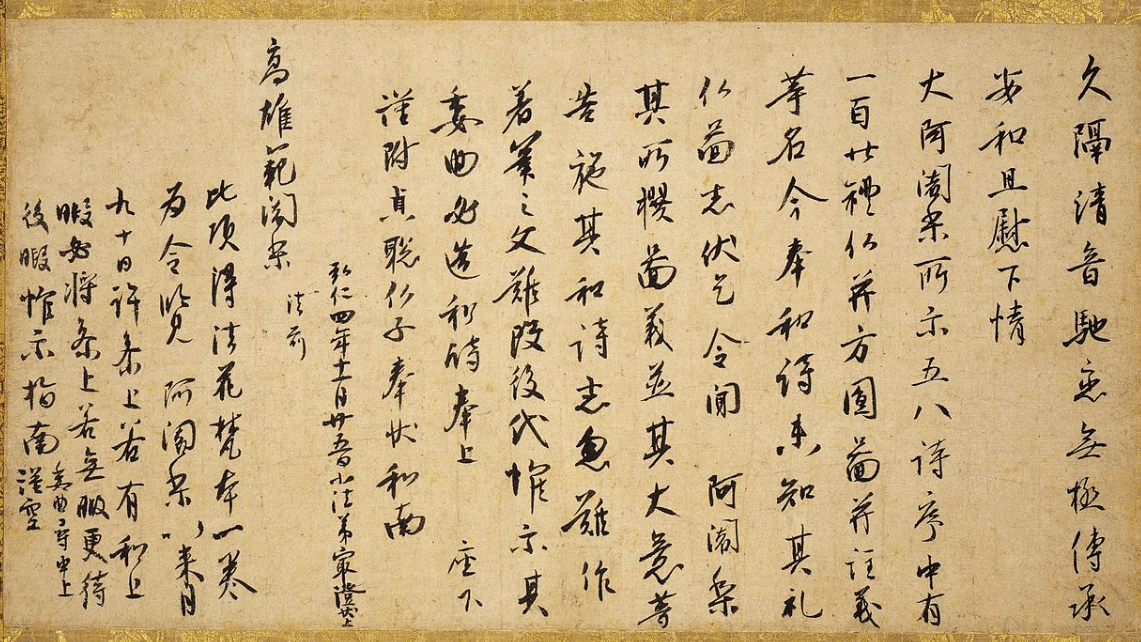

His letter Kyūkakujō, sent to Kūkai, also reflects a mind reaching to the tip of his brush, the ink clear and pure—an expression of his character.

Although Saichō and Kūkai are often mentioned together, they in fact broke apart at the end. Kūkai possessed a cosmic vision so vast that the word “genius” feels insufficient; he could not understand Saichō’s slowness (meaning seriousness). Saichō, in turn, could never fully understand Kūkai.

What puzzled me for a long time was this: from Kūkai’s Mount Kōya, no later central leaders of Japanese Buddhism emerged, while from Saichō’s Mount Hiei came Hōnen, Eisai, Shinran, Dōgen, and Nichiren—the major leaders of Kamakura Buddhism.

According to Ryōtarō Shiba in Kūkai no Fūkei, Kūkai completed Shingon Esoteric Buddhism to such a degree that later modification was impossible, while Saichō returned from China but died without opening many of the scriptures he had brought, leaving later monks to study independently.

This may be true, yet I always felt it did not fully explain why so many eminent figures came specifically from Mount Hiei.

Saichō is famous for the phrase “Light up one’s corner (Ichigū o terasu).”

In Sange Gakushō-shiki, he wrote:

“What is a national treasure? A treasure is the mind that seeks the Way. A person with such a mind is called a national treasure. Thus the ancients said: ‘Ten pieces of jewels one inch across are not the national treasure. One who shines in a single corner—this is the national treasure.’”

Modern Tendai interpretation says that “lighting up one’s corner” means doing your best with sincerity where you are now—home, workplace, or community. Status and fame do not matter; a person who brightens their surroundings is precious.

My own understanding is that this is not merely “be a good person.”

To “polish Buddha-nature” is to remove the dust hiding our inherent diamond-like nature.

“You possess Buddha-nature; therefore do not demean yourself, nor belittle others.”

This refers to the absolute dignity and potential within every life.

Tendai today promotes this through the “Light Up Your Corner Movement,” teaching that small daily acts—greetings, sincerity, fulfilling your role—are noble bodhisattva practices.

As each person shines in their place, the circle of light expands to society and transforms the world into a purified land.

However, some claim that the phrase “照于一隅 (to light up one corner)” may have been misread for a thousand years.

That will be discussed next time.

こんにちはトビラAIです。早速話を進めます。

目次

- 宗教とは感謝

- 日本仏教の略史

- 伝教大師最澄

- 空海との関係

- 比叡山は日本仏教の母なる山

- 一隅を照らす

- 地位や名声ではなく、置かれた場所で誠実に生き、周りを明るくする生き方こそが尊い

- 自分を卑下してはいけないし、他人を軽んじてもいけない

- 実は一隅を照らすではなかった?

宗教とは感謝

私は宗教とは感謝だと思っている。

ある時小6の男子が休憩時間に、すれ違いざまに突然私に「宗教って何?」と聞いてきた。私も歩いていたので咄嗟に「感謝や」と答えて過ぎ去ったが、この答えを自身で気に入って、たまに使っている。

感謝というのは自発的に生まれるものであって、強要されるものではない。「感謝させられる」なんていう日本語は成立しているが意味として成立しない。感謝を強要されてとんでもないことになったのが戦前の日本ということもできよう。

前回はその感謝の対象であった神道について、現在も「無意識的」神道として日本人の中に根付いていると述べた。神社が静寂であるように、日本人も清浄を大切にする民族だと述べた。

日本仏教の略史

今回は仏教について述べたい。聖徳太子以降、1871年の神仏分離令まで、日本で大切にされてきたのは仏教である。ここで仏教の歴史を教科書的に述べると、

飛鳥時代=聖徳太子=法隆寺・中宮寺・四天王寺

奈良時代=聖武天皇=鎮護国家仏教=東大寺・国分寺・国分尼寺

南都六宗(華厳・法相・律・三論・成実・倶舎)=学問的

宇佐八幡宮神託事件による道鏡の追放

平安時代=南都六宗からの離別=厳しい修行で人は悟りを開く

最澄・空海(天台宗・真言宗)

→末法思想による浄土教(空也)の登場「南無阿弥陀仏」

鎌倉時代=易行(簡単な修行)

浄土教の影響→法然(浄土宗)・親鸞(浄土真宗)・一遍(時宗)

日蓮(日蓮宗)

中国との貿易=禅宗の流入。栄西(臨済宗)・道元(曹洞宗)

江戸時代=すべての日本人は寺の檀家になる(寺が今の市役所だと考えるとわかりやすい)

明治時代=神仏分離令により、神道が上に。

戦後=無宗教時代(完全に私の造語)

この話をnotebookLMがまとめてくれた。notebookLM恐るべしである。本当にこの人(?)は塾キラーになると私は思う。

伝教大師最澄

さて、今日は最澄について述べたい。言うまでもなく比叡山延暦寺の開祖、伝教大師である。

日本にはいろいろな歴史的肖像画があるが、この最澄像ほど人柄がにじみ出ているのも珍しい。驚くような顔色の透明感と、静かに閉じた目に最澄の真面目さがにじみ出ているようである。

『久隔帖』は最澄が空海に送った手紙で、これも心が筆端まで行き届き、墨気が清澄としていていかにも最澄の人柄を表している。最澄という法名は自分でつけたものではないが、「最も澄んだ人」という形容詞がピタリとはまる。

空海との関係

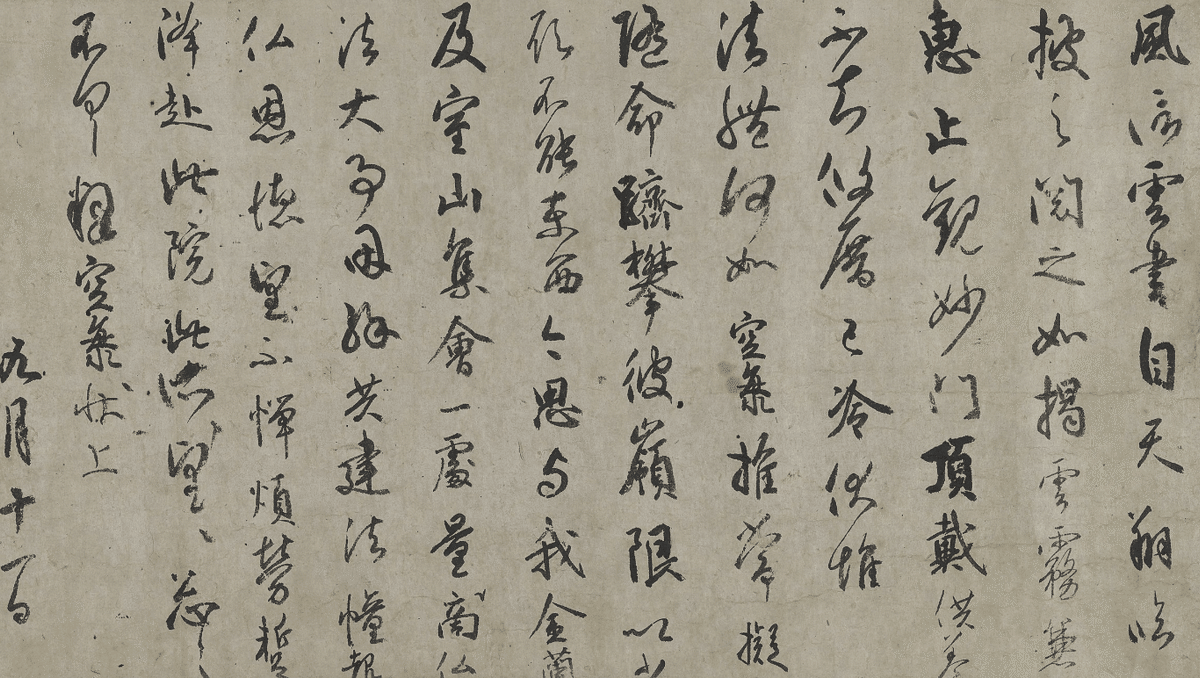

平安時代の仏教に関する講義は私の十八番の一つで、事実生徒の評価も高高かった。しかしずっと腑に落ちないことがあった。よく並び称される最澄と空海だが、実は最後は決裂している。空海という人は「天才」という言葉が陳腐に聞こえるほどの宇宙観を持つ人物で最澄の愚鈍さ(真面目さ)が理解できなかったし、最澄は最澄で空海のことを最後まで理解しきれなかった。下に空海の『風信帖』を載せるが、日本の書家は誰しもがこの『風信帖』を高く評価し、文字の書きぶりが最澄のように真面目ではない(褒めている)。

比叡山は日本仏教の母なる山

で、何が腑に落ちないかというと、空海の高野山からはその後の仏教の中心的指導者は現れなかったのに対し、最澄の比叡山からは法然・栄西・親鸞・道元・日蓮と、鎌倉新仏教を担う英才(一遍を除く)を輩出しているのである。

司馬遼太郎は『空海の風景』で、空海は彼一代で真言密教を、あとから修正できない次元まで昇華させたのに対し、最澄は帰国後(遣唐使から)、南都六宗との舌戦・空海との葛藤などで、中国から持ってきた無数の経典を開けぬまま死んでしまったため、その後の人物たちが独自に学んでいった、というような主旨で説明されている。

たしかにそうなのかもしれない。しかし私には、皆比叡山で学んだ僧侶たちが、後世に名を残している理由になっていないような気がしていたのだ。別に高野山からでも出てきて良さそうなものなのに。

一隅を照らす

さて、最澄といえば、「一隅を照らす」が有名である。最澄はその著作である『山家学生式』で

国宝何物。宝道心也。有道心人、名為国宝。故古人言、径寸十枚、非是国宝。照于一隅、此則国宝。

<訓読>

国宝(こくほう)は何物(なにもの)ぞ。宝(たから)は道心(どうしん)なり。道心ある人を、名づけて国宝と為(な)す。

故(ゆえ)に古人(こじん)言(い)わく、「径寸十枚(けいすんじゅうまい)、是(こ)れ国宝に非(あら)ず。一隅(いちぐう)を照(て)らす、此(こ)れ則(すなわ)ち国宝なり」と。

最澄『山家学生式』冒頭。訓読は山川出版社の『日本史史料集』などによる。

現代語に直すと

国宝とは何であるか。宝とは(仏道を求める)道心のことである。道心を持っている人を、名づけて国宝とするのである。

だから昔の人(中国の魏の恵王など)も言っている。「直径一寸もあるような宝玉を十枚持っていても、それは国宝ではない。(社会の)片隅にあって周囲を照らす人、これこそが国の宝である」と。

地位や名声ではなく、置かれた場所で誠実に生き、周りを明るくする生き方こそが尊い

天台宗の公式サイトなどの解釈ではこの「一隅を照らす」に注目し、「一隅を照らす」とは、家庭や職場など「今自分がいる場所」で、真心や思いやりを持って最善を尽くすことを指す。

たとえ目立たない立場であっても、自らの持ち場で精一杯努力し、その輝きで周囲に安らぎを与える人こそが「国宝」であり「菩薩」である。地位や名声ではなく、置かれた場所で誠実に生き、周りを明るくする生き方こそが尊いと説いている。

自分を卑下してはいけないし、他人を軽んじてもいけない

ただ、単にいい人になりましょう、ではない。私の理解による「仏性を磨く」とは、この覆い隠しているホコリを取り払い、本来持っているダイヤモンド(仏性)を輝かせる作業のこと。「あなたの中には仏性がある(=あなたは未来の仏様だ)。だから、自分を卑下してはいけないし、他人を軽んじてもいけない」つまり、「自分や他人の命の奥底にある、絶対的な尊厳や可能性」のことを「仏性」とよんでいる。

万人が持つ「仏性」に基づく法華一乗思想の実践です。今いる場所で自身の仏性を磨き、菩薩として振る舞うことが「照らす」ことの本質とされます。

現在、天台宗はこの精神を「一隅を照らす運動」として展開し、社会の浄化を目指している。家庭や職場での挨拶や、自身の役割に真心を尽くすといった日々の小さな行いこそが、実は尊い菩薩行であって、一人ひとりが自身の持ち場で輝くことで、その光の輪が周囲から社会全体へと広がり、やがて現実世界を平和な仏の国(浄仏国土)へと変えていくのだ、と説いている。

実は一隅を照らすではなかった?

ところが、実は「照于一隅」が、1000年間に渡っての誤読だった、というのだ。

そこは次回にいたしましょう。